Before implementing any nudges, we needed to know the employees’ current behaviour while descending the stairs. Therefore, an initial observation of 1,275 people was performed on two different locations. Furthermore, a survey of 142 employees was conducted in order to better understand why people performed as they did. Here are two examples of what the employees answered:

› 68.9% of the employees reported that they did not consider their behaviour to be unsafe.

› 65.3% of the employees reported that they did not think about their behaviour while they were doing it.

And just as we would expect (and fear), the findings strongly indicated that the employees didn’t act in a safe manner on the stairways because:

1. they had a low risk-perception of using the stairs and

2. they were not aware of their own actions while descending the stairs.

Therefore, a nudge that could both increase risk perception and raise awareness of the risk factors seemed like an appropriate solution.

Figure 1: Illustration of ´the Dead Person Silhouette´ – This is not the final result but merely shows the idea behind the intervention

Dead Person Silhouettes were implemented at the bottom of the company’s stairs at two test locations [1]. One of the expected effects of the Dead Person Silhouettes was to influence employee risk perception by making them imagine, just for a second, the consequences of falling down the stairs. Although the solution may seem dramatic at first, the intervention was considered much less invasive than forcing employees to watch videos of people falling down stairs.

In addition to the Dead Person Silhouettes, thought bubbles were placed by the silhouettes and at the top of the stairs. This was done in order to capture the attention of employees before they descended, as well as, provide employees with statements that hinted towards the preferred behaviour e.g. “Should have grabbed the handrail”.

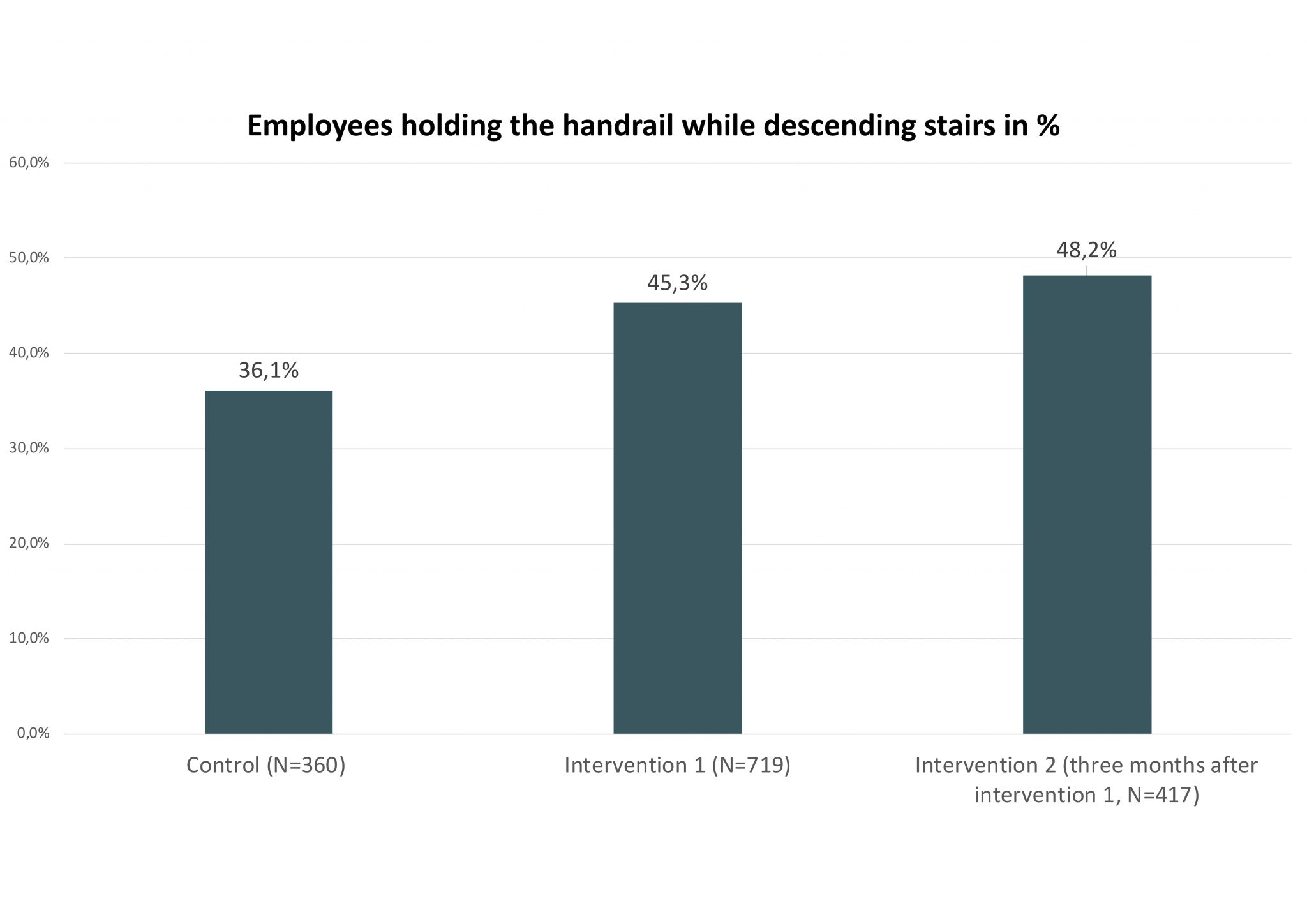

The foundation of this experiment was built upon an observational study of 1,079 employees descending the company’s stairs. The first measurement we performed was the control measurement, showing us that 36,1% of the employees initially used the handrail on their way down the stairs. Hereafter, we implemented the silhouettes on the floor, which resulted in a statistically significant increase of 9,2%-points (from 36,1% to 45,3%) (p=0.0038) (see figure 2).

After three months, we returned to the company in order to test the intervention’s long-term effect. This time, we observed that 48,2% of the employees were using the handrail while descending the stairs. This increase was, however, not statistically significant (p=0.3514).

Figure 2: Shows an increase in the number of employees using the handrail

Figure 2: Shows an increase in the number of employees using the handrail

The results of this experiment show how a simple and cost-effective solution is capable of nudging employees to act in a safer manner while descending stairs.

In addition to these results, we were also excited to see that the intervention made employees perform other types of safe stairway behavior, such as, walking at a slower pace and paying more attention to each step of the stair.

The company is currently working on sharing the intervention within the organisation and encourage other locations to implement the silhouettes. The intervention has received much positive feedback.

We hope you liked this post and that the project may inspire more of you, and your organisation, to consider a behavioural approach to reach even higher safety standards.

References:

[1] World Health Organization (2016). Falls. Media Centre.

[2] Jacobs, J. V. (2016). A review of stairway falls and stair negotiation: Lessons learned and future needs to reduce injury. Gait & posture, 49, 159-167.

[3] INTERNATIONAL SHARK ATTACK FILE – Risk of Death: 18 Things More Likely to Kill You Than Sharks

[4] Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive psychology, 5(2), 207-232.

[5] Pinker, S. (2011). The better angels of our nature: Why violence has declined (Vol. 75). New York: Viking.

[6] Scott, A. (2005). Falls on stairways: literature review. Health and Safety Laboratory.